The other day I was browsing through Ancient Near Eastern Texts Relating to the Old Testament (ANET), edited by James B. Pritchard (3rd ed. with supplement, 1969). Like it sometimes does, the itch crept up on me to learn how these texts survived to reach me over thousands of years, and I decided to do a deep dive.

I’ve spent a great deal of time teaching myself paleography, the study of ancient writings. I like the thrill of feeling like I’m discovering something lost, possibly even hidden, especially when the writing is indecipherable to the English eye. I spent a good deal of time in college familiarizing myself with Akkadian cuneiform. I’m working on Chinese. I’ve even fully collated, translated, and edited several Greek and Latin manuscripts. But I’ve never touched Egyptian hieroglyphs, so I thought to myself, why not give it a try?1

What a time to be alive when nearly all of the sources are available online! I thought I’d blog the process of tracking them down, and here we are. Enjoy a meandering walk through deep archives of long-forgotten documents!

Picking a Hieroglyphic Text

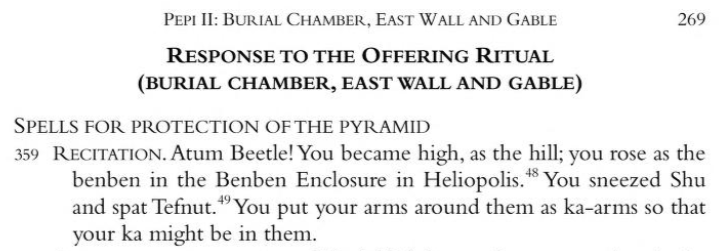

Although ANET has been superseded in many respects by more recent collections,2 it remains a very accessible volume and one that I frequently use as a starting point. The first text in ANET’s Egyptian myths section is an ancient Egyptian creation myth, translated by John A. Wilson (p. 3). According to the notes, the text was inscribed in pyramids in the Sixth Dynasty, or around 2300 BCE. That’s 4300 years ago, for those keeping score at home.

I’ve included only a snippet for reference, since the text is still under copyright. As you can see, the text is still pretty difficult to understand, and outdated to boot.

The notes clarify a little bit, but I had to do some Google-fu to get more details: Atum–Kheprer is the god of the rising sun (represented by a scarab), the “ben-bird” is a heron or other heron-like bird representing a kind of proto-phoenix, and the “ben-stone” is something like a monument in the “Ben-House” or temple in Heliopolis – the City of the Sun. Shu and Tefnut are the deities of air and moisture, respectively. Ka was the spiritual essence of life.

All of that makes a little more sense with some extra details from ancient Egyptian religion, but – to be completely honest – my focus was less on the religion and more on the paleography.3

Getting My Feet Wet in Egyptology

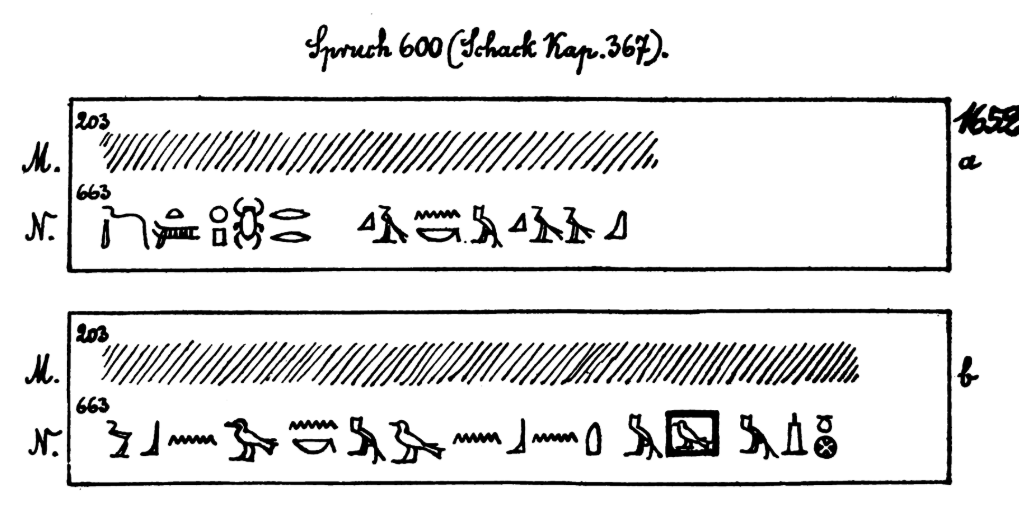

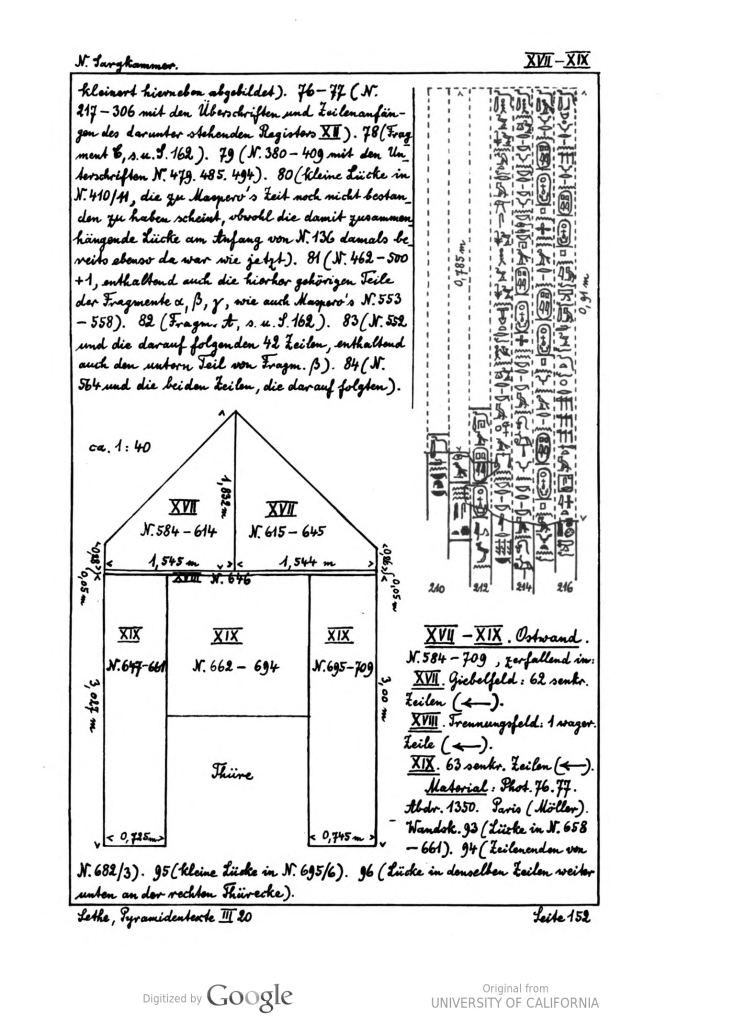

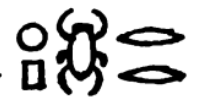

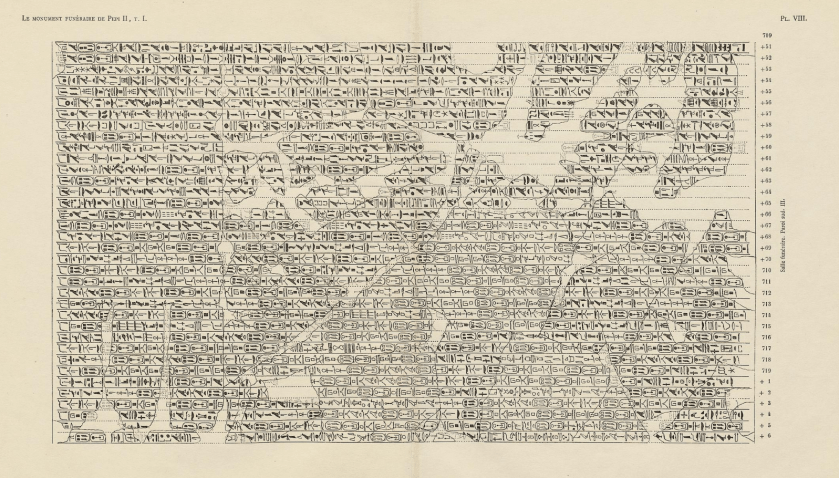

The first thing I wanted to find was a physical source – the actual artifacts that the text comes from. I’d have to work backwards from what I had. Fortunately, ANET provided the source for the hieroglyphic text: K. Sethe, Die altägyptischen Pyramidentexte, volume 2 (1910), sections 1652-1656, which I was able to find at HathiTrust. Here’s a screenshot of the first few lines:

So that’s a pretty good start. I’ve already found a source for the hieroglyphic text. However, I have two concerns:

- First of all, I still have no way of understanding how the hieroglyphics are translated into English text. Are the translations very literal? How did we decipher hieroglyphics in the first place?

- In addition, Sethe’s transcription is a secondary transmission at best. What if he mistranscribed something? I’d much rather have a photograph of the original artifacts.

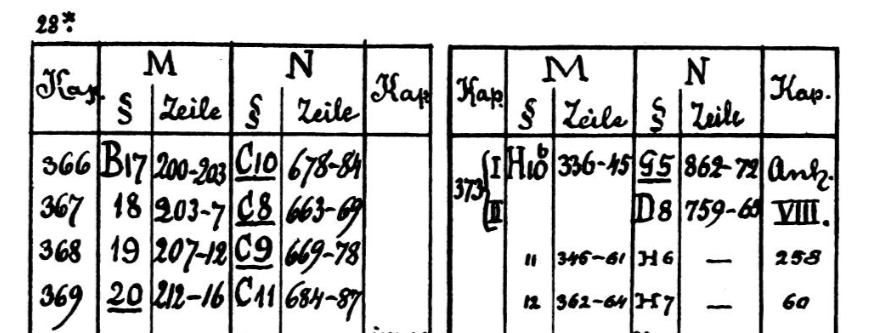

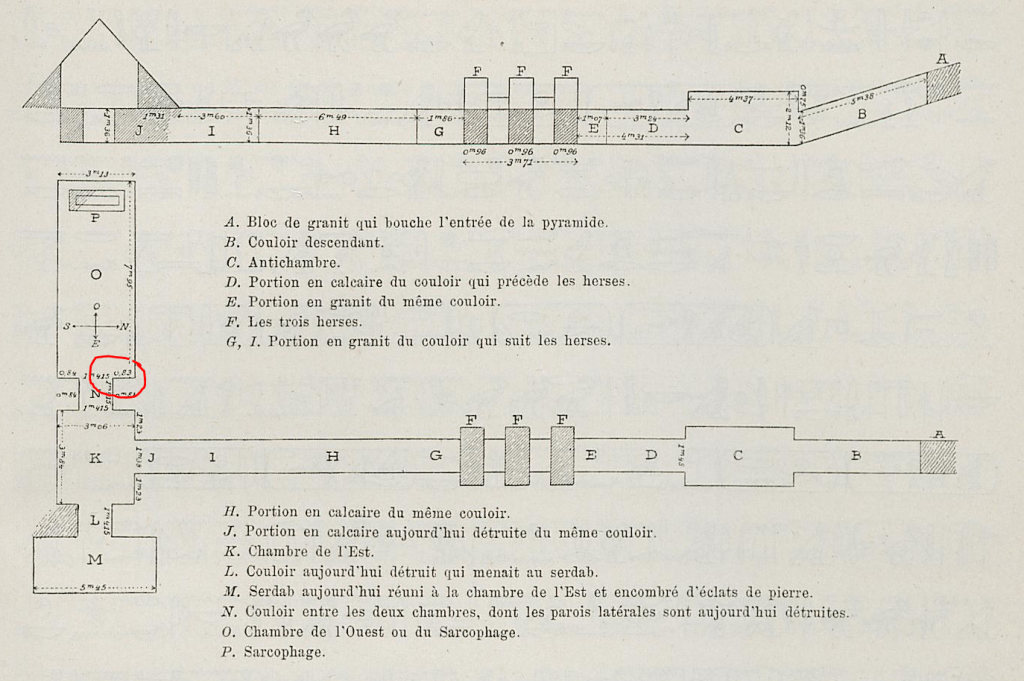

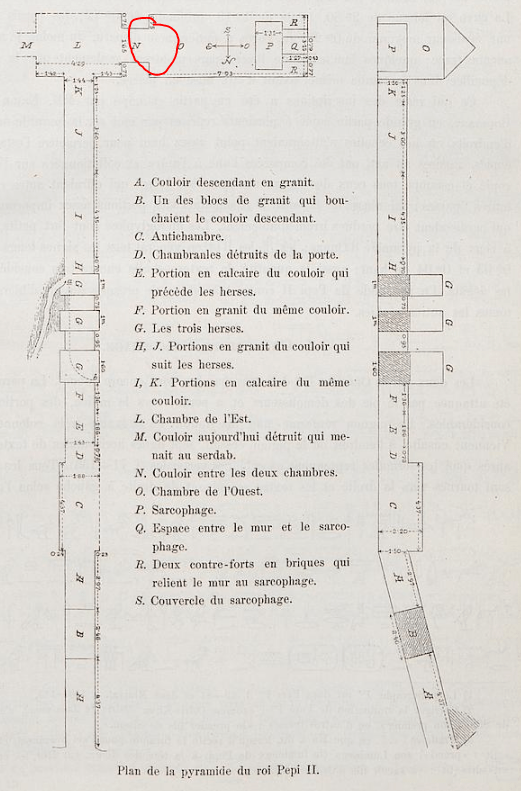

I had to browse around the front matter a little bit to figure out what “M” and “N” meant – they are, respectively, the Pyramid of Merenre and the Pyramid of Pepi II. These seem to have been the standard sigla for the pyramids4 – “Schack” apparently is a reference to Hans Schack-Schackenburg, Aegyptologische Studien, volume 2 (1902) which I found at Archive.org: here’s the reference to “Schack Kap. 367” in said volume.

The “Chapter” numbers of Schack-Schackenburg appear to have been the leading reference numbering for these texts (prior, they were solely referred to by Pyramid and Line) before Sethe’s numbering took precedence. I wasn’t able to glean any more from Aegyptologische Studien, so I was back to Sethe.5

By now I had come to understand that this inscription was part of a fluid corpus of ancient Egyptian texts known as the Pyramid Texts, which originated in the very early 3rd millenium BCE (ca. 2800 for some of the oldest). As I came to understand, in the early 1880s Gaston Maspero discovered two pyramids (our “M” and “N”, of course) at Saqqara in Egypt – a very, very old but not the oldest part of ancient Egypt – and soon found that they shared texts. He published these texts from 1887-1893. Schack-Schackenburg apparently took an interest in them for linguistic purposes and correlated them in 1902. Sethe completed the inventory in 1910.

Armed with this knowledge, I was able to track down a bibliography: Thomas George Allen, Occurrences of Pyramid Texts with Cross Indexes of These and Other Egyptian Mortuary Texts (1950). This furnished me with references to further descriptions of the primary sources.

For “M”, the Pyramid of Merenre (ca. 2280 BCE):

- The original excavation reports and hieroglyphic transcription by Gaston Maspero: RT6 9 (1887), p. 177; RT 10 (1888), p. 1; RT 11 (1889), p. 1

- Sethe (already referenced)

- In addition, I’m aware of a new edition from Mission archéologique française de Saqqâra (MAFS), Isabelle Pierre-Croisiau’s Les textes de la pyramide de Mérenrê, but I was unable to find a copy.

For “N”, the Pyramid of Pepi II (ca. 2250 BCE):

- Again, the original report and transcription by Gaston Maspero: RT 12 (1890), p. 53; RT 14 (1893), p. 125

- Sethe (already referenced)

- Additions to Maspero’s reconstruction by Gustave Jéquier, Le monument funéraire de Pepi II, Volume 1: Le tombeau royal (1936). This provides no additional material about the east wall of the burial chamber, so it isn’t greatly relevant.7

Tracing the Physical Sources

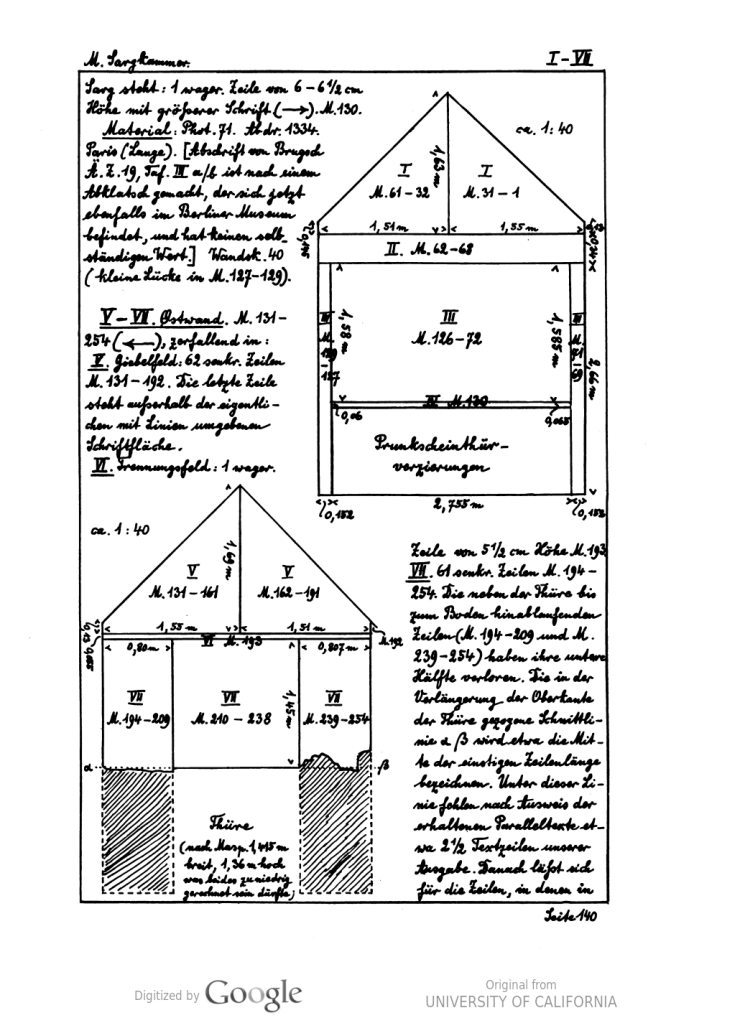

Before attempting some of the other sources, I browsed around Sethe a little more to see if he recorded anything else about M and N. Indeed, volume 3 is a detailed description of the pyramid chambers, with some schematics and sketches. Unfortunately, no photographs are reproduced.

These panels are briefly described, and Sethe notes his sources: mainly, photographic reproductions in the Egyptian Museum of Berlin, which I can locate in accession logs, but unfortunately haven’t been digitized.

With a dead-end in Sethe, I proceeded to Maspero.

Ultimately, the trail on photographs went cold there. I wasn’t able to find any in secondary Egyptological reference works, either. This documentary is actually the best visual look inside the tombs that I’ve been able to locate at all. You can see the correspondence between the diagrams and some of the interior shots / models in the video.

A Better English Translation

So I’d found copies of the original hieroglyphic text, as close to the actual artifacts as I could get. But I still didn’t know what to do with the hieroglyphs. How would I even start to look them up?

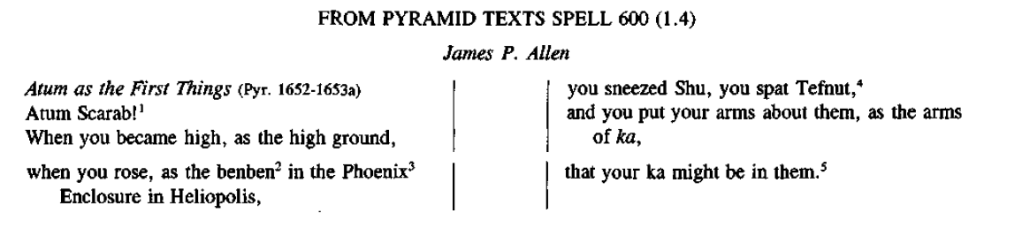

As I was browsing for a modern translation of the Pyramid Texts, I found James P. Allen‘s amazing volume, The Ancient Egyptian Pyramid Texts (2005), which renders the sample excerpt thus:8

Allen’s concordance provided further confirmation that M and N are the only sources for Pyramid Text 600, so with that, I felt confident that my quest for primary sources was as close to complete as it could be.9

Allen’s glossary provided a transliteration of “Kheprer” (rendered “Beetle” in the translation above) that was more intelligible to me than hieroglyphics: ḫprr. I had no fricking clue what a ‘ḫ‘ was, but this was something a lot closer to recognizable. This was the first indication that hieroglyphics might represent something pronounceable. Just from having a little linguistic background, I figured this was a phonetic transcription of some kind – an indication of how the word was spoken, rather than how it was written.

Getting a Transcription

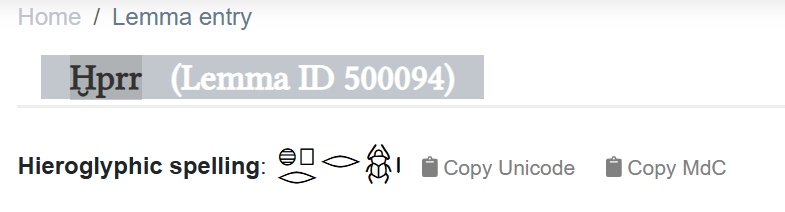

Searching for an Egyptian hieroglyphic dictionary, I was of course led to the monumental Thesaurus Linguae Aegyptiae. And lo and behold, the first thing I find is a search tool where I dutifully enter my “ḫprr” and immediately find myself at the dictionary entry for it: Ḫprr.

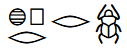

The body of the page confirms: this sign means the divine name “Kheperer.” And this  is fairly close to the symbols we see in Sethe:

is fairly close to the symbols we see in Sethe:  but slightly rearranged. So… like… why is that possible? Why is that sequence of signs “Ḫprr”? And why is it rearranged?

but slightly rearranged. So… like… why is that possible? Why is that sequence of signs “Ḫprr”? And why is it rearranged?

With the Wikipedia article on Egyptian hieroglyphs as a basis, I learned that everything but the beetle sign is a “uniliteral” – a sign representing a single sound. So ![]() is ‘ḫ’ (a ‘kh’ sound),

is ‘ḫ’ (a ‘kh’ sound), ![]() is ‘p’, and

is ‘p’, and ![]() is ‘r’. So that’s most of the transliteration.

is ‘r’. So that’s most of the transliteration.

However! There’s more to it than that – what is the scarab beetle doing in the word? It’s not a uniliteral. As it turns out, hieroglyphic words sometimes contained redundancies to assist the reader. They’re called “phonetic complements,” and that’s what the scarab is. A scarab sign by itself could be enough to indicate the name “Kheprer”, but the uniliterals fully clarify the meaning. And so, the  is indeed “Ḫprr” with the scarab logogram couched inside its own phonetic transcription!

is indeed “Ḫprr” with the scarab logogram couched inside its own phonetic transcription!

Apparently hieroglyphics were never standardized. It was kind of just… up to the scribe to determine how to represent words. I was somewhat familiar with that from studying cuneiform, which also melded phonetic and logographic usages of the same signs and could also be wildly subjective to the whims of a particular scribe. (I don’t recall a logogram ever being infixed in its own syllabic breakdown.)

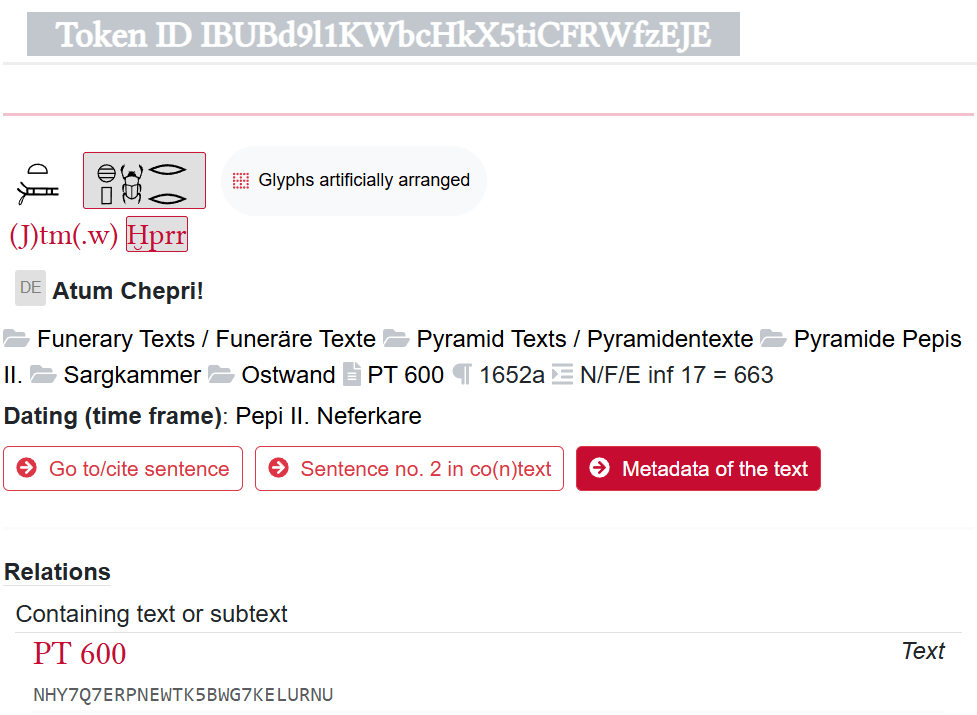

The TLA page does indeed list  as a variant spelling, and it even provides links to source texts. And what do you know – one of the cited texts is our very own PT 600!

as a variant spelling, and it even provides links to source texts. And what do you know – one of the cited texts is our very own PT 600!

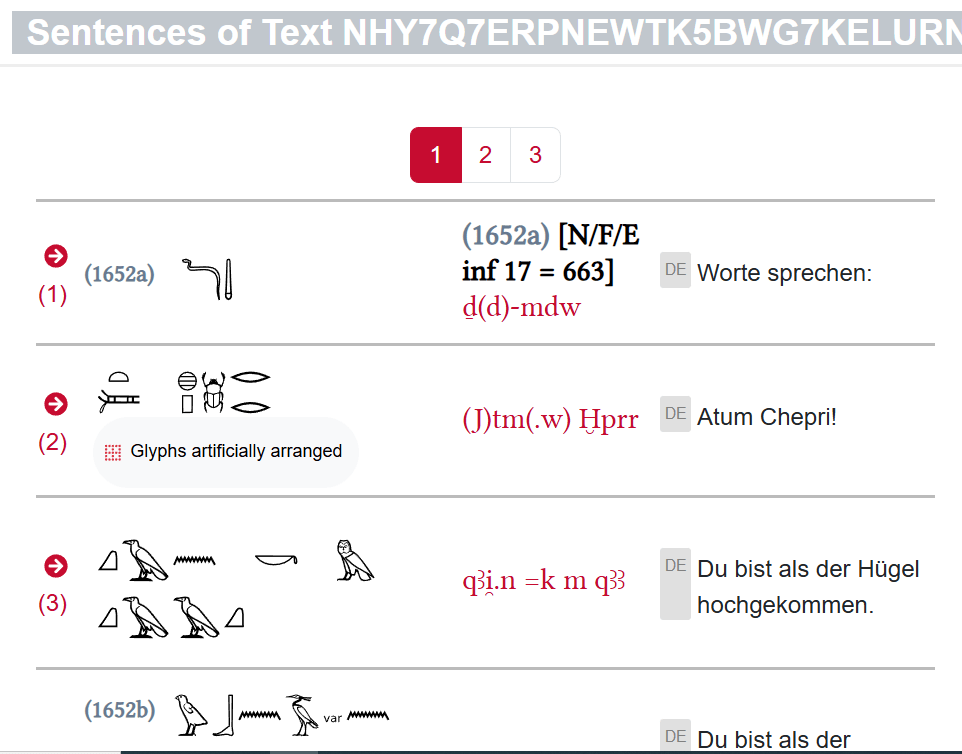

And if we follow the link for “sentence no. 2 in context” we get the whole pyramid text, fully transcribed in glorious Unicode hieroglyphics! You can go back to Sethe or even Maspero and see how the signs match.

I plan on digging a lot deeper into hieroglyphics. Now that I’ve figured out how to work from a source text to a translation, the next step is getting familiar with the language and working out a few examples myself (always, of course, relying on professional scholarship to verify my work – it would be very Dunning-Kruger of me to think that a couple hours of curiosity, however erudite, puts me on a similar level of competency). However, I’ve learned to at least understand several ancient languages by following the scholarship like this – verifying my hypotheses by matching sources to professional translations. A useful skill? Almost certainly not 😆 but one that keeps me entertained.10

- My time spent dabbling in the realms of textual scholarship culminated in a personal software project to create a web app for collecting, transcribing, collating, and editing texts. I’ll definitely write more on that at some point, but for now it’s too embryonic. ↩︎

- See, for example, The Context of Scripture: Canonical Compositions from the Biblical World, eds. Hallo and Younger, volume 1, pp. xxiv-xv. ↩︎

- Usually I’d prefer more advanced sources than Wikipedia, but this is why I’m keeping it light. ↩︎

- These are cited in ANET, but I was more curious whether a) it was accurate, and b) whether any new discoveries had been made in the last 60 years. ↩︎

- This was extremely hard to decipher from the text of Aegyptologische Studien, which, I assume, is a lithographic reproduction of a handwritten document. I can barely interpret German as it is, so throwing old handwriting in the mix was nearly confounding. Die altägyptischen Pyramidentexte is also a difficult lithograph, but I wasn’t about to let myself be defeated by German of all things while attempting to decipher literal hieroglyphs 🤣 ↩︎

- Recueil de travaux relatifs à la philologie et à l’archéologie égyptiennes et assyriennes. ↩︎

- But it’s still hella cool to look at:

↩︎

↩︎ - Allen had also provided the translation in The Context of Scripture, vol. 1, eds. Hallo and Younger, 2003, pp. 7-8, but I prefer the newer one:

↩︎

↩︎ - As I finish writing this post, I also found Allen’s A New Concordance of the Pyramid Texts, 2013, which contains a full transcription of PT 600 in volume 5. ↩︎

- After all was said and done, I found a delightful Cambridge history, A History of World Egyptology (2021), eds. Bednarsky, Dodson, and Ikram. I have access through an institutional subscription, but I’m seriously considering buying a copy. Basically every name that I’ve hyperlinked to Wikipedia throughout this post is covered in this volume! ↩︎

Leave a comment